St Anger - Metallica

$ 13.99 – $ 20.99

Metallica's first new material in over five years arrived after a flurry of non-musical activity that included a much-publicized spat over Internet file sharing, the departure of bassist Jason Newsted, and a lengthy stay in rehab for James Hetfield that suspended the recording of a new album indefinitely.

Hetfield returned to the fold in late 2001.

Still without a bass player, Lars Ulrich, Kirk Hammett, and their newly sober frontman recruited longtime producer Bob Rock to man Newsted's spot, and creation of the album commenced in May 2002.

St.

Anger arrived a year later as a punishing, unflinching document of internal struggle -- taking listeners inside the bruised yet vital body of Metallica, but ultimately revealing the alternately torturous and defiant demons that wrestle inside Hetfield's brain.

St.

Anger is an immediate record.

Written largely in the first person, it never warns of impending doom, doesn't struggle with claustrophobia, and has care neither for religion's safety nor its hypocrisy.

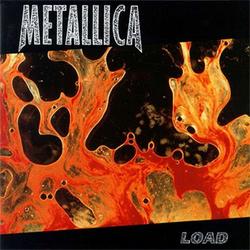

(The religious symbolism of its title and artwork seems only to function as a metaphorical device.) Lacking the heavy metal baggage of these past themes, Metallica is left to ponder only itself and its singer's psychosis, and delivers its diagnosis on slabs of speed metal informed with years of innovation and texture.

The record exists as it ends.

As the lockstep thrash of the eight-plus minute "All Within My Hands" tumbles toward its final gasp, Hetfield is explicit in his aims.

"I will only let you breathe my air that you receive," he seethes.

"Then we'll see if I let you love me." Ulrich's drums sputter in fits and starts, but the guitars are already dying, shutting down as Hetfield stabs at the microphone.

"Kill kill kill kill kill," he screams, and you have to check the wall for a splatter radius.

It's a brutal, ugly end to an album that switches on like a bare light bulb in an underground cave.

It blasts each corner with harsh, unfiltered light for 75 minutes, until the bulb is shattered with a combat boot, leaving disquieting after-images exploding on the backs of your eyelids.

"Frantic" is driven forth by a snare drum that just may be made of iron, Hammett and Hetfield's guitars eschewing separate parts in favor of a roaring tag-team approach.

A hint of the band's mid-'90s nod to alternative drifts in during a bridge, but it's quickly swallowed alive by the song's muscular groove, never to be heard from again.

"St.

Anger," the single, marks the first appearance of a vocal technique that lurks in the shadows throughout the album.

As Hetfield groans, "I feel my world shake/It's hard to see clear," he seems manipulated by an unseen force, flickering like bad reception.

It's unsettling, and startlingly effective.

Hetfield's psyche is on trial throughout, and though he often expresses confusion and anger over his struggle ("Some Kind of Monster" and especially "Dirty Window," in which he becomes both judge and jury), the mechanistic rhythms of the band seem to give him strength.

"Shoot Me Again" -- another seven-minute epic -- becomes Hetfield's sneering answer to himself.

It lurches into gear, juxtaposing a deceptively soothing verse with a dirty guitar line that explodes in the song's titular money shot.

The resonating cymbal cracks during its stops and starts are particularly satisfying, as you can imagine the members of Metallica facing each other in a circle, jamming the song's jagged melody down the throat of a solitary microphone.

(The image comes to life in St.

Anger's bonus DVD edition, which captures Hetfield, Hammett, Ulrich, and new bassist Robert Trujillo in their headquarters compound, shredding through each song on the album in its entirety.) St.

Anger isn't a comeback, and it's not a throwback.

The album is exactly what Metallica needed to make at this point in its career, after clawing its way to the top of the metal scrap heap, reeducating a generation of bands, and popularizing its genre beyond anyone's expectations.

St.

Anger looks inward with a hard eye, and while it finds some grinning demons in that pit, it also unearths some of the sickest grooves of Metallica's 20-plus-year lifespan.

| Title/Composers | Performer | Listen | Time | Size | Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FranticKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:50 | 13 MB | 40 MB |

| 2 | St. AngerKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 07:21 | 16 MB | 53 MB |

| 3 | Some Kind of MonsterKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 08:25 | 19 MB | 58 MB |

| 4 | Dirty WindowKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:24 | 12 MB | 37 MB |

| 5 | Invisible KidKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 08:30 | 19 MB | 58 MB |

| 6 | My WorldKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:45 | 13 MB | 39 MB |

| 7 | Shoot Me AgainKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 07:10 | 16 MB | 50 MB |

| 8 | Sweet AmberKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:27 | 12 MB | 36 MB |

| 9 | PurifyKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:13 | 11 MB | 37 MB |

| 10 | All Within My HandsKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 08:47 | 20 MB | 61 MB |

| 11 | FranticKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:50 | 13 MB | 40 MB |

| 12 | St. AngerKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 07:21 | 16 MB | 53 MB |

| 13 | Some Kind of MonsterKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 08:25 | 19 MB | 58 MB |

| 14 | Dirty WindowKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:24 | 12 MB | 37 MB |

| 15 | Invisible KidKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 08:30 | 19 MB | 58 MB |

| 16 | My WorldKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:45 | 13 MB | 39 MB |

| 17 | Shoot Me AgainKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 07:10 | 16 MB | 50 MB |

| 18 | Sweet AmberKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:27 | 12 MB | 36 MB |

| 19 | The Unnamed FeelingKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 07:09 | 16 MB | 46 MB |

| 20 | PurifyKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 05:13 | 11 MB | 37 MB |

| 21 | All Within My HandsKirk Hammett, James Hetfield, Bob Rock, Lars Ulrich | Metallica | Play | 08:47 | 20 MB | 61 MB |

| 143 mins | 327 MB | |||||

| 143 mins | 997 MB | |||||

| Artist | Job | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jason Bridges | Editing Assistant |

| 2 | Anton Corbijn | Photography |

| 3 | Scott Cunningham | Production Coordination |

| 4 | Mike Gillies | Assistant, Digital Engineer |

| 5 | Kirk Hammett | Composer, Group Member |

| 6 | Dave Hatchet | Camera Operator |

| 7 | Mike Hatchet | Camera Operator |

| 8 | James Hetfield | Composer |

| 9 | Connie Isham | Script Supervisor |

| 10 | Wayne Isham | Director |

| 11 | Brad Klausen | Production Design |

| 12 | Logan Lebo | Gaffer |

| 13 | Tracy Loth | Editing |

| 14 | Dana Marshall | Producer |

| 15 | Vlado Meller | Mastering |

| 16 | Metallica | Primary Artist, Producer |

| 17 | Colin Mitchell | Camera Operator |

| 18 | Paul Owen | Monitors |

| 19 | Nick Pectol | Camera Operator |

| 20 | Jean Pellerin | Camera Operator, Editing |

| 21 | Alex Poppas | Photography Director |

| 22 | Pushead | Cover Illustration |

| 23 | Bob Rock | Composer, Engineer, Mixing, Producer |

| 24 | Greg Rodgers | Editing |

| 25 | Ryan Smith | Camera Operator |

| 26 | Robert Trujillo | Bass, Group Member |

| 27 | Lars Ulrich | Composer, Group Member |

| Quality | Format | Encoding | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | MP3 | 320kps 44.1kHz | MP3 is an audio coding format which uses a form of lossy data compression. The highest bitrate of this format is 320kbps (kbit/s). MP3 Digital audio takes less amount of space (up to 90% reduction in size) and the quality is not as good as the original one. |

| CD Quality | FLAC | 16bit 44.1kHz | FLAC is an audio coding format which uses lossless compression. Digital audio in FLAC format has a smaller size and retains the same quality of the original Compact Disc (CD). |